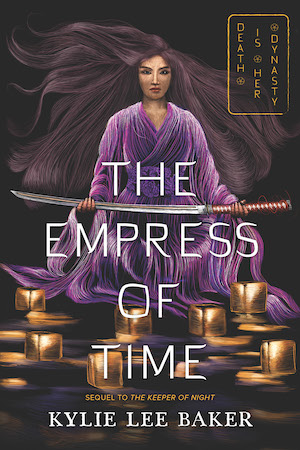

Death is her dynasty.

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from The Empress of Time, the second book in the Keeper of Night duology by Kylie Lee Baker, publishing with Inkyard Press on October 4th.

Ren Scarborough is no longer the girl who was chased out of England—she is the Goddess of Death ruling Japan’s underworld. But Reapers have recently been spotted in Japan, and it’s only a matter of time before Ivy, now Britain’s Death Goddess, comes to claim her revenge.

Ren’s last hope is to appeal to the god of storms and seas, who can turn the tides to send Ivy’s ship away from Japan’s shores. But he’ll only help Ren if she finds a sword lost thousands of years ago—an impossible demand.

Together with the moon god Tsukuyomi, Ren ventures across the country in a race against time. As her journey thrusts her in the middle of scheming gods and dangerous Yokai demons, Ren will have to learn who she can truly trust—and the fate of Japan hangs in the balance.

EARLY 1900S

TOKYO, JAPAN

Buy the Book

The Empress of Time

In the last nights of the nineteenth century, the humans began to whisper about a new demon, hungrier and crueler than all the rest.

The Yōkai hunted where shadows grew deep, in the thin breath of twilight that bridges night and day. It crawled from the spindly shadows of chair legs on hardwood floors, the crooked shade that lamps cast on wallpaper, even your own silhouette—the one shadow you could never escape.

But none of those things were really shadows at all.

They were holes carved into the human world, peering into a void that echoed down and down through an endless night. Its darkness could peel away your skin like you were a soft summer peach, crawl deep in your bone marrow and rot you from the inside out, soak the soil with your blood. The night stole the parts of you that no one wanted—all your lies and broken promises and disappointments.

From these holes, the Yōkai clawed its way up and up into the stark light of a new world. Then all of the terrors that night’s veil normally concealed—the things you were never meant to see—were laid bare. The Yōkai’s jaw swung open like an unlatched gate and it began to feast.

The police always arrived too late, long after the echoes of screams had faded away and the blood had run dry, leaving dark stains across the floor. They would find no clues at all, no broken doors or windows, no fingerprints or stray hairs, as if the monster had never even existed. The only pattern between the deaths was the state of the bodies: rib cages opened up like books, organs spilled across the floor, and hearts mysteriously absent.

So the humans prayed to gods who couldn’t intervene even if they’d wanted to, made shrines to benevolent Yōkai, and lit one thousand lights to banish the shadows. But none of it made any difference, because it wasn’t a Yōkai at all.

It was me.

I came to Tokyo on a night of gray rain, carrying one knife and a list of one hundred names, my lips cracked and dry from all the blood I’d scrubbed off them. I hated rainy days because the clouds dispersed the sunlight and weakened the shadows, leaving me to travel most of the way by foot.

Today, a man whose name I couldn’t remember was going to die. All I knew was that he rowed boats full of opium smuggled from Formosa up and down the canals of Ginza, a crime that even humans would punish by death.

Chiyo, my servant who managed the records of both the living and dead, had handpicked him and ninety-nine others for execution today, as she did every day. Every morning, she handed me a list of names, and every evening I returned with all of them crossed out, their souls in my stomach and their blood splashed across my kimono.

This was not, strictly speaking, something a Death Goddess was supposed to do.

Though I hadn’t exactly received a Death Deity Handbook the moment I’d stabbed my fiancé, Hiro, in the heart and inherited his kingdom, I was fairly certain that I wasn’t meant to collect souls long before their Death Days just to make myself more powerful. My Shinigami were supposed to be the ones who wandered among the living, dragging souls down to the banks of Yomi and devouring their hearts in my stead, each soul another drop in the dark sea of my power.

That was what Izanami, my predecessor, had done for thousands of years. That was what my fiancé had intended to do. That was what any honorable god would have done.

But there was no honor in sitting on a stolen throne.

My Shinigami always whispered that I wasn’t really their goddess anyway, so what did it matter if I made my own rules? The deep darkness demanded payment, and ten years of souls hadn’t been enough. If my Shinigami wouldn’t bring me more, I would do it myself.

At least all the humans on my list were men who had strangled their wives or women who had poisoned their children, abusers and molesters and criminals who were too smart to get caught by the police. Chiyo kept careful files and judged them impartially, presenting me a list of her selections, carefully spread across Japan so that the humans could never find any pattern. Generally, I trusted Chiyo to know what I wanted, but that was one order I had given explicitly: that none of the humans on her list were innocent.

It wasn’t because I was kindhearted, or thought I had a divine right to pass judgment on Earth’s sinners, or anything so noble as that.

It was because one day, I would eat enough souls that I would be strong enough to bring my brother back from the deep darkness, and I would have to look him in the eye and explain exactly how I’d done it. If I told him his life had been bought with the blood of innocents, he’d probably walk straight back into the void and let the monsters devour him rather than live with that debt on his soul.

I would carry the debt for him, so he would never have to know how heavy it was.

I melted into the shadow of a passing streetcar, letting it carry me closer to Ginza, the smell of wet pavement and oil sharp beneath the wheels. It wasn’t the rainy season, but my presence often darkened the sky wherever I went, wringing hot mist from the clouds.

As I passed through the streets, the humans stiffened and looked around, wondering why their skin suddenly prickled with goose bumps, why their hearts beat faster, why the crowds around them had become faceless and the sounds of the city had faded into a thorny static. Humans could sense when Death was coming, but for most of them, it would be no more than a fleeting sensation. Fewer humans stayed out at this hour, especially in the heavy late-summer heat, and more of them began to disperse as I passed them.

In the ten years since I’d come to Japan, the cities had started to fill up with echoes of London—streetcars with hand-crank engines that sputtered down the roads, railroad officers in Western suits and flat-topped straw hats with black ribbons, women carrying alligator leather handbags. My old life was following me, crossing the ocean piece by piece.

I saw the changes more in the crowded streets of Tokyo than in the farming villages, which was one reason I avoided urban areas as much as I could. That, and everything in the city felt just slightly off balance, like the sheer number of humans had tilted the Earth off its axis. Everything in the market leaned precariously away from the buildings—all the bright canopies over storefronts, the lantern garlands, the bright painted posters over the theaters—making the crowded streets even smaller by narrowing the sky overhead into a thin strip of white. Even the lotuses in the city’s central park seemed to tilt to the left, ignoring the pull of the sun.

The humans here must have sensed who I was, but none of them would look me in the eye. The hot days of summer cast a humid haze over the distance, blurring the far ends of the streets so that everything in the distance was a dizzy secret. Children bounced balls in street puddles of gray water too murky to show their reflections. Men rushed around pulling jinrikisha with crates that might have contained rice or pottery or contraband. It was a city of mysteries and possibilities, not all of them good.

I jumped off the streetcar and grabbed onto the shadows below a stone bridge that stretched over the canal, stepping waist-deep into tepid brown water. Men paddled up and down the still stream, boats piled high with mysteries beneath black tarps, bobbing unhurriedly away. No one sat on the docks that lined the canals, driven away by the choking humidity wafting off the waters.

At 8:34, according to the silver-and-gold clock chained to my clothes, a man with a gray face and green gloves rowed his boat under my stone bridge.

He would never make it to the other side.

I clenched a fist around my clock, and the whole street held its breath.

The gentle lapping of the canal against its stone barriers went silent, the waters turning to glass. The distant hum of mosquitoes and faraway calls of street vendors disappeared.

I looped my clock’s chain around my hand a few times to bind it to my palm, then hauled myself onto the boat, my skirts heavy with the foul water.

The man had become a statue in the time freeze, his skin the color of unbaked clay under the shadows of the bridge, his eyes red and pupils as thin as pinpricks. With the touch of my hand around his throat, he awoke.

He thrashed against my grip, rocking the boat dangerously to the side. But the shadows tore themselves from the waters and strapped the boat down with their long arms, holding us steady.

“It’s faster if you stay still,” I said, pulling a knife from my left sleeve. I always offered humans this advice, but they rarely listened. This man was no exception.

He moved to grab my sleeves as if to throw me from the boat, but before he could, more shadows came unstuck from the mossy walls of the stone bridge and dragged him down until he was sprawled atop his smuggled opium. Now that I ruled over the Realm of Perpetual Darkness, all the shadows in the world obeyed me. They knew what I wanted, and they did not hesitate.

“Who are you?” the man said, choking out each word as he fought the shadows wrapped around his throat.

I said nothing, because I didn’t know what answer he wanted. I was the monster that humans whispered about at night. I was a Shinigami and a Reaper and a murderer. I was a goddess who he would never worship because he didn’t even know I existed. And I was Ren, but I didn’t want a human to call me that. No one had called me that in a decade. No one dared to. These days, it was just “Your Highness.”

The human thrashed against my shadows, but they held him tight.

“What do you want?” he said.

Ah, now that was a better question.

“Your soul,” I said.

His eyes went wide, his jaw clenched tight. “Well, you can’t have it!”

“I wasn’t asking your permission,” I said, drawing my knife.

Once the glow of the setting sun reflected off my blade, the human began to fight in earnest. I had all the darkness of the underworld at my disposal, but it was a simple mortal weapon that scared him the most. How amusing.

“Why?” he said. “Why me?”

I kicked aside a corner of his tarp, gesturing to the many black boxes beneath it. We both knew what was inside.

“Why do you care?” he said. “Why do I deserve to die for this?”

“It’s not about what you deserve,” I said, frowning. “It’s about what I need.”

Then I sliced a line down his chest, splitting his shirt in half so it wouldn’t get in my way.

His eyes went flat, his opium-shrunken pupils somehow eating all the color from his irises, his whole body vibrating with fear.

I was used to fear in humans’ eyes at the end of their days, for I’d spent hundreds of years collecting souls as a Reaper. But this was different, and the humans must have sensed it too, because they always fought harder and longer. Today wasn’t this man’s Death Day, and his body knew it, sensed the wrongness of it, and fought back like creatures of the deep sea dragged up to land.

But who was going to stop me?

Now that Hiro was dead, there was no higher power in Yomi anymore. My only adversary was the invisible wall a thousand miles high that barred me from the deep darkness.

While my servants could venture past it unimpeded, Death could not. When Izanami had ruled Yomi, her husband, Izanagi—the father of Japan and ruler of the living—had built the wall to stop her from entering the deep darkness. Those who destroyed Death inherited her kingdom, and if the monsters beyond the wall devoured Izanami, they would take her throne and all the souls in Japan. Now I was the new Izanami, and the wall would not yield for me either. At least, not yet.

For over a decade, I’d sent my guards beyond the wall to search for Neven in the darkness, but every day they returned empty-handed. I’d decided that no matter what rules Izanagi had laid down thousands of years ago, I needed to grow strong enough to break them. I couldn’t rely on anyone else to save Neven.

Maybe it would take a thousand more souls, or a million more, or all the souls in Japan to make me strong enough. Whatever the cost, I would pay it. If I kept taking and taking, then one day, I would throw my fists against that great invisible barrier, and the wall would crumble into a thousand pieces. I would finally cross into that land of drowning darkness and bring my brother home.

Excerpted from The Empress of Time by Kylie Lee Baker, Copyright © 2022 by Kylie Lee Baker. Published by Inkyard Press.